Global warming has all but guaranteed that storm seasons will continue to intensify, in traditional hurricane hot spots and further afield, meaning more people are likely to be affected by destroyed homes and communities and in need of financial support. But there is never enough support to go around, so charities are always looking to donate as efficiently as possible. A partnership between GiveDirectly and Google.org aims to smooth the process of delivering funds to the people who require them most urgently.

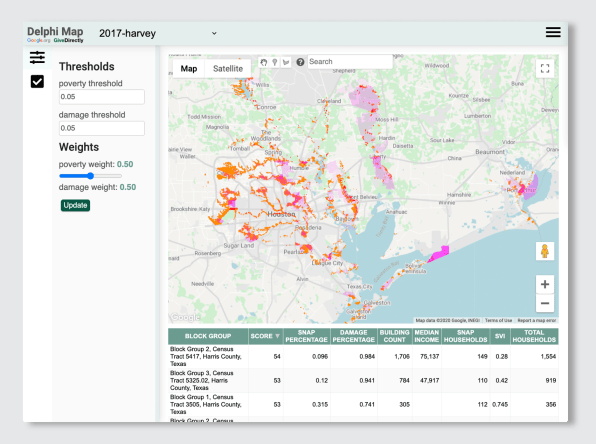

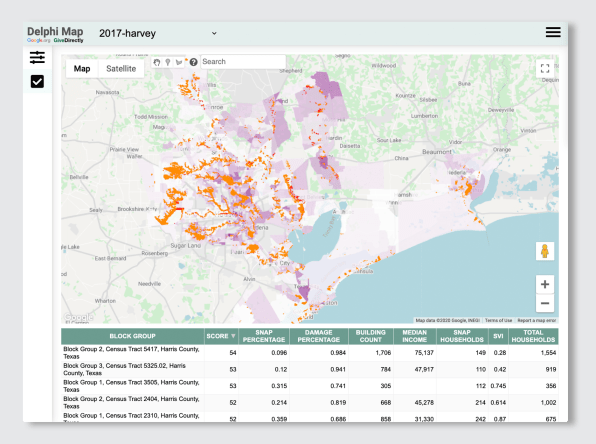

The charity, the largest in the world that assists via direct cash transfers only, and the tech giant have launched Delphi, an online tool that allows aid organizations to pinpoint the specific locations, down to granular zip-code level, most in need of assistance. The data-driven effort creates scores based on the overlap between two metrics—poverty level and destruction of property—then ranks and shows those neighborhoods visually in Google Maps.

The organization used the tool retrospectively to assess their distribution efforts for Harvey, which caused approximately $125 billion worth of damage. “In retrospect, if we had had the tool, we would have been able to make sure that these marginalized communities were not missed,” says Alex Nawar, humanitarian director at GiveDirectly.

Before the development of the new product, GiveDirectly principally used on-the-ground techniques to find the most crippled communities. They relied on media coverage, phone calls, on-the-ground searches, and information collected by other organizations. That proved to paint inaccurate pictures, often leaving less visible communities disregarded. “This tool would have really made sure that no one was left behind because they were not part of the narrative, or not part of the word-of-mouth campaigns,” Nawar says.

GiveDirectly would then target those communities with direct cash relief. The charity only sends money transfers, typically on prepaid debit cards, because that allows people to decide for themselves how to spend the money on recovery. Sending clothing, for instance, can clog up supply lines; food donations can go bad; and it’s hard to donate vital items such as building materials. It’s also simply less patronizing. “Traditional aid has some paternalistic bent to it,” says Alex Diaz, head of crisis and humanitarian response at Google.org, “but the notion of direct cash transfer, at its core, acknowledges the dignity and agency within recipients.”

Delphi, which is now live, will not be limited to GiveDirectly. It has the framework to be used not only for hurricanes but also for other disasters, such as wildfires. Nawar adds that it’ll also save aid organizations time, and field costs by about 25%, by cutting back on the laborious fieldwork. Recently, the American Red Cross expressed interest in trialing it, and Diaz hopes—having made it open-source and easy to use—that it’ll ultimately benefit the humanitarian sector as a whole.