Trump's FEMA wasn't ready for last year's record-breaking hurricane season, and it wants the public to know that it's not ready for another one.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency was already supporting 692 federally declared disasters when hurricane season started last year. Then came the most destructive disaster season in U.S. history, causing $265 billion in damage and forcing more than a million Americans from their homes. FEMA was overwhelmed.

Most Popular

So the agency has a novel suggestion for Americans as the 2018 disaster season heats up: Don’t rely on us.

In a report last week evaluating its response to last year’s disaster, FEMA details “how ill-prepared the agency was to manage a crisis outside the continental United States, like the one in Puerto Rico,” The New York Times reported. “And it urges communities in harm’s way not to count so heavily on FEMA in a future crisis.”

“The work of emergency management does not belong just to FEMA,” the agency stated near the end of the report. “It is the responsibility of the whole community, federal, [state, local, tribal and territorial governments], private sector partners, and private citizens to build collective capacity and prepare for the disasters we will inevitably face.”

The sentiment echoes President Donald Trump’s own comments about Puerto Rico last year, following the devastation wrought by Hurricane Maria.

Still, it’s probably good advice, because thousands of people who depended on FEMA for help last year are still struggling. They include 83-year-old Rosalea Nall, who lived in a hotel for eight months after her Texas home was flooded during Hurricane Harvey. Last week, she had to move back into her gutted house after FEMA stopped providing housing vouchers for Harvey victims. They also include the more than 1,700 Puerto Rican refugees of Hurricane Maria, currently living in hotels on the mainland, whose housing assistance is set to expire on July 23 (and which would have expired on June 30, but for the grace of a federal judge). Meanwhile, approximately 1,000 people in Puerto Rico remain without electricity.

FEMA acknowledged many of its failures in last week’s report—notably that it emptied emergency supplies from a Puerto Rico warehouse just days before Maria hit. (The supplies were sent to the U.S. Virgin Islands, then reeling from Hurricane Irma.) As USA Today put it, the agency admitted its planning “was incomplete, did not adequately account for the possibility of multiple major disasters in a short amount of time, and underestimated the impact of ‘insufficiently maintained infrastructure’ in Puerto Rico.”

But FEMA also argued that an effective response was near-impossible given its resources. “FEMA entered the hurricane season with a [workforce] less than its target, resulting in staffing shortages across the incidents,” the report read. The agency has approximately 10,000 employees, but last year’s hurricanes and wildfires “collectively effected more than 47 million people—nearly 15 percent of the Nation’s population.”

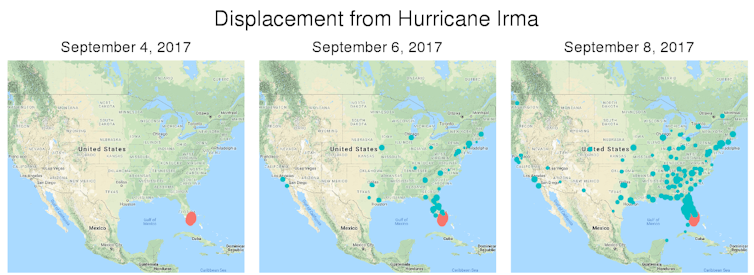

Nearly 5 million households registered for FEMA assistance in 2017—more than the previous 10 years combined, and more than all who registered for assistance from hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, and Sandy combined. The wildfires in California were their own behemoth, requiring more federal response contracts than Hurricanes Harvey and Irma combined. FEMA’s response to Hurricane Maria was also “the longest sustained air mission of food and water delivery in FEMA history,” according to the report. Hurricane Irma was “one of the largest sheltering missions in U.S. history,” with 6.8 million people under evacuation order. Eighty percent of the households impacted by Hurricane Harvey did not have flood insurance, either, contributing to FEMA’s high costs.

FEMA thus was only able to pay for less than 10 percent of the destruction. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria caused a combined $265 billion in damages, according to the report. Yet as of April 30, FEMA had only obligated $21.2 billion toward those damages.

The agency offered several recommendations for improving FEMA’s capability for this year’s disaster season, which is already underway. It suggested, for example, “enhancements to the planning process” when collaborating with state and local governments before disasters. FEMA essentially echoed the message from its planning report in February: “The most important lesson from the challenging disasters of 2017 is that success is best delivered through a system that is Federally supported, state managed, and locally executed.”

FEMA is certainly correct that disasters must be managed at all levels, but the most important lesson of the 2017 disaster season is that weather disasters are becoming more frequent and more damaging. The government’s failure to grapple with that reality contributed to FEMA’s poor response. For example, the 1988 Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act—the law that gave FEMA its authority to coordinate disaster relief efforts—ensured that the agency could only re-build Puerto Rico’s weak electricity system after it was wiped out by Maria; it was not allowed to spend money on rebuilding a more resilient electricity system.

FEMA could have suggested a change in that law in its after-action report. And yet, just as the agency failed to mention climate change in its February report, it failed to do so in last week’s report. Extreme weather is getting more extreme, and until FEMA recognizes and acts on that reality, it will find itself overwhelmed indefinitely.

source: https://newrepublic.com