The strongest earthquakes that strike the planet, such as the 9.0-magnitude earthquake that hit Japan last year, occur at particular "hotspot" points of Earth's crust, a new study finds.

The strongest earthquakes that strike the planet, such as the 9.0-magnitude earthquake that hit Japan last year, occur at particular "hotspot" points of Earth's crust, a new study finds.

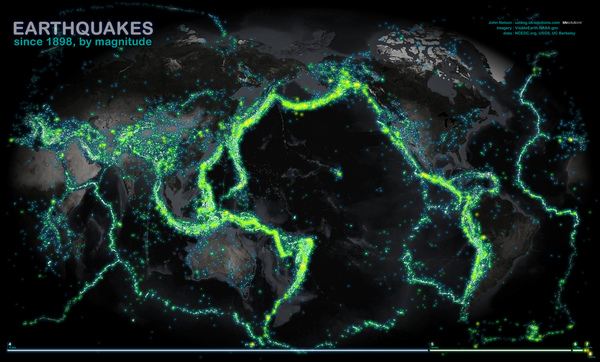

About 87 percent of the 15 largest earthquakes in the last century occurred in the intersection between specific areas on spreading ocean plates, called oceanic fracture zones, and subduction zones, where one tectonic plate slides underneath another, according to the paper, published recently in the journal Solid Earth. The scientists used a data mining method to find correlations between locations of earthquakes over the last 100 years, the strength and geological origin.

The bottom of the ocean is crossed by underwater ridges, such as the mid-Atlantic ridge, which runs north to south between the Americas and Africa. These ridges divide two tectonic plates that move apart as lava emerges, solidifying and creating new rock. The midocean ridge jogs back and forth at offsets known as transform faults, creating zigzag-shaped plate boundaries. Fracture zones are scars in the ocean floor left by these transform faults.

These fracture zones are often marked by large underwater mountains with valleys between them. Millions of years after forming in the middle of the ocean, these mountains slowly advance all the way to a subduction zone, often at the opposite end of the sea. The researchers hypothesize that these submarine mountains "snag" as they enter subduction zones, causing an enormous amount of pressure to build up over hundreds or thousands of years before finally releasing and creating huge earthquakes, according to the study.

These areas — where the mountains of fracture zones are forced beneath another plate — are prone to earthquake "supercycles," where large earthquakes happen every few hundred or few thousand years, said Dietmar Müller, a study author and researcher at the University of Sydney, in a statement.

Many of these areas may not be known to be particularly risky, since seismic hazard maps are constructed mainly using data collected after 1900, he said. For example, the area that spawned Japan's deadly 9.0-magnitude Tohoku quake in 2011 was not predicted to be of significant risk by previous hazard maps, according to the study.

"The power of our new method is that it does pick up many of these regions and, hence, could contribute to much-needed improvements of long-term seismic hazard maps," Müller said.

While 50 of the largest earthquakes in the past 100 years have also happened in the fraught regions between these fracture zones and subduction zones, the connection doesn't seem to hold for smaller quakes, according to the study. That's because other faults aren't "blocked" in the same way by large underwater features, and don't need to accumulate as much stress before faulting, the researchers say.

The paper hasn't officially been peer-reviewed, although many scientists have commented on the study online. "I ?nd the evidence of positive correlation presented in this paper convincing enough," wrote one scientist. "Given the small amount of data available, the authors have developed an interesting way of testing for correlations."

source: http://news.yahoo.com